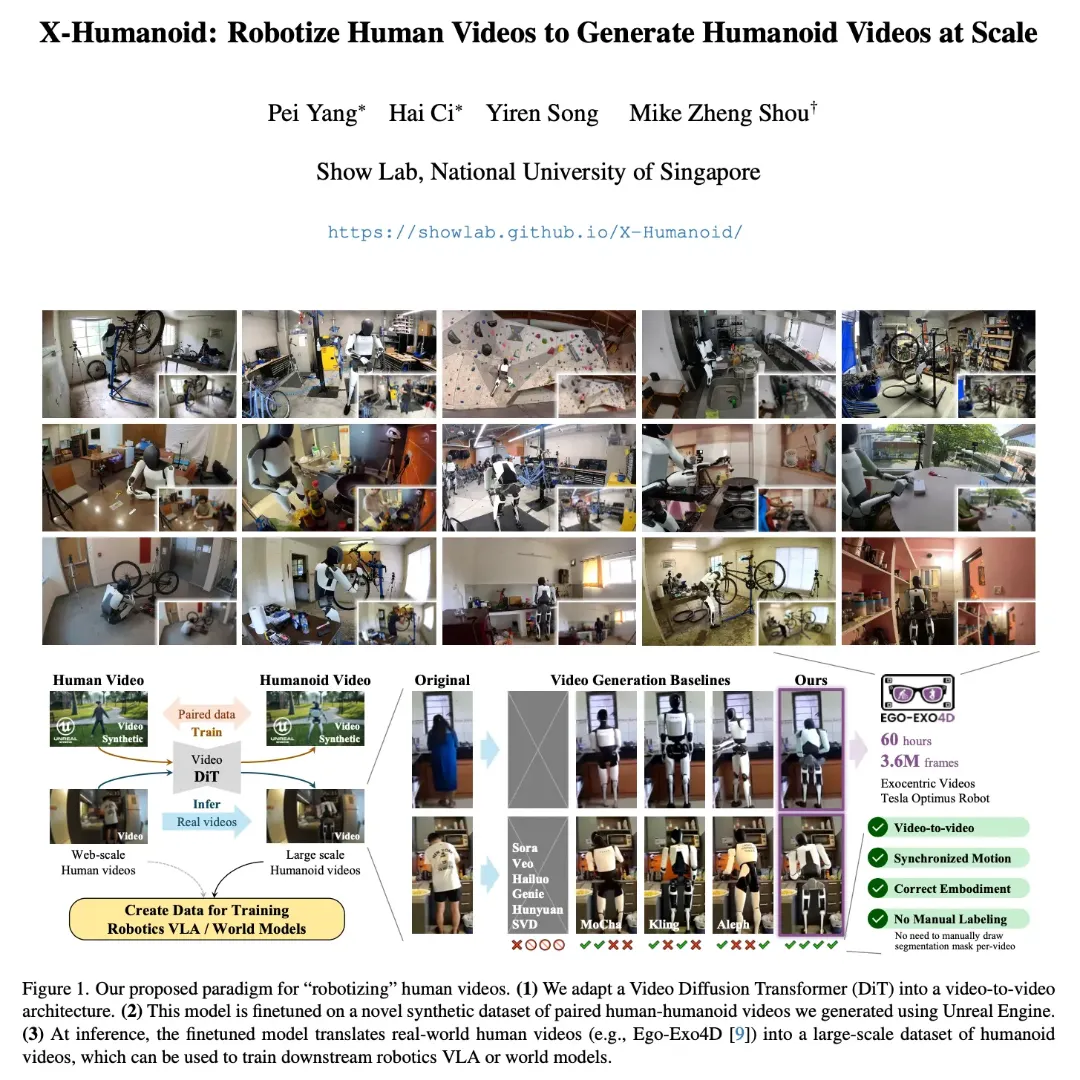

A growing number of research teams are exploring interesting ways to address a bottleneck, the scarcity of robot data. The premise is simple. Take abundant human video → convert it into humanoid motion → train Vision-Language-Action (VLA) models at scale.

This is a clever response to data scarcity, but it exposes a deeper truth, the real bottlenecks in humanoids are embodiment and physics. Tesla’s Optimus shows this clearly despite massive data, world-class AI, factory access, and full stack control, it remains limited to constrained, slow, contact-light tasks. This isn’t a failure of video learning, but a limit of what human-to-humanoid videos can teach.

“Robotized human video” pipelines can generate visually convincing humanoid motion. The results often look impressive. But robots don’t fail because motion looks wrong, they fail because it is physically infeasible. Human movement uses flexible muscles, small adjustments, and balance reflexes, while humanoids have rigid joints, torque limits, and narrow stability margins. A generative model can create a trajectory that looks fine in video, but if it exceeds actuator limits by 5%, it can be catastrophic for the hardware and the system.

Neither human videos nor robotized videos encode grip force, normal forces, friction coefficients, or impact transients. This is exactly where real robots struggle most. Tesla’s Optimus can fold clothes, sort objects, and move bins only after extensive use of teleoperation, force-torque sensing, conservative motion planning, and slow closed-loop control. Video-derived data helps perception and pose priors. It does not teach a robot how hard to push, pull, or grasp.

The promise of these approaches is scale millions of demonstrations. But humanoids don’t fail at the 50th percentile. They fail at the 99.9th percentile. A 1-2% error rate is acceptable in generative video. It is unacceptable for embodied systems operating near balance, torque, and safety limits. This is why real deployments progress task-by-task, environment-by-environment, even with enormous data availability.

These pipelines still require adaptation for each robot morphology. That’s not a detail, it’s the core problem. Changes in limb length, actuator placement, or mass distribution sharply degrade learned policies. Even with a single humanoid design, training once and deploying everywhere remains out of reach.

Bottom Line

“Robotized human video” pipelines are great, but only for perception bootstrapping, motion initialization, and simulation augmentation. They are not a shortcut to general-purpose humanoids. Until learning systems internalize physics, contact, and failure, not just pixels, humanoids will remain impressive demos rather than deployable systems.